A Legend - All But Lost to History

Alexander G. Clark (1826-1891), was a barber, a lawyer, newspaper editor, and an activist - and an U.S. Minister to Liberia. His many achievements have gotten little mention in the annals of Iowa history and certainly in the history of the United States.

Alexander G. Clark might be best known for his efforts to assist his 12-year-old daughter Susan, in her quest to gain entrance into the Muscatine (Iowa) public schools. Officially Susan Clark was the plaintiff in a lawsuit filed in 1867, and she won. That suit allowed Susan Clark to attend public school and prohibited segregated schools across Iowa. It was the first decision in the United States to declare segregation unconstitutional. This was 86 years before the United States would rule favorably in the Brown vs Board of Education landmark ruling. In fact, the attorneys presenting the case before the supreme court used the Clark case as a precedent setting ruling to support their case. For more information about the Iowa Supreme Court Decision - Clark V Bd of Directors, 24 Iowa 266 (1868) see https://libguides.law.drake.edu/Clark150.

Muscatine School Named After Susan Clark

In 2019 when the Muscatine School Board combined 2 middle schools, they decided to name the new junior high school in honor of the first Black to graduate from Muscatine High School, Susan Clark Junior High opened for the 2020-21 school year.

A year later, Alexander Clark, worked for the passage of amendments to the Iowa Constitution (Amendments of 1868) which struck the word "white" from provisions in the constitution, involving electors, census, senators, apportionment, and the militia. However, it wasn't until 1880 that the words "free white" were removed from provisions relating to the legislative department. This amendment effectively gave African American men the right to vote in Iowa, two years before the U.S. granted that right with the 15th amendment.

During his lifetime, Alexander G. Clark won a historic court case, played a pivotal role in moving Iowa into an era of civil-rights for Blacks, helped recruit Black soldiers for the Union during the Civil War, and served his last days as the U.S. ambassador to Liberia.

Muscatine observes “Alexander Clark Day” on his birthday, February 25th.

Settled in Muscatine in 1842

Alexander G. Clark (February 25, 1826 – May 31, 1891), the son of former enslaved people - was born to John and Rebecca Darnes Clark in Pennsylvania. When he was 13 he joined his uncle, William Darnes, in Cincinnati, Ohio where his uncle taught him the barbering trade. He got a job as a barber on the steamboat, The George Washington. At age 16, Clark came to Bloomington, Iowa (later known as Muscatine*) on that steamboat, and opened a barber shop. Barbering would be his main occupation for 20 years. He became involved in other endeavors as well - including suppling wood for the boats moving up and down the Mississippi. He grew vegetables on the timberland that he cleared. He invested in real estate and parlayed his money into a sizable fortune.

Iowa's black codes were harsh at the time but Clark saw Iowa as an opportunity. In 1848 (October 9), Alexander G. Clark (age 22) married Catherine Griffin of Iowa City. Catherine had been enslaved, in Virginia, until the age of 3. Together they raised three children, Rebecca, Susan, and Alexander G. Clark, Jr. (two other children died as infants).

That year (1848) was also the year that Clark joined 33 others in establishing the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church**.

More Work for Anti-slavery and the Union

Clark was a friend of Frederick Douglass, becoming a distributor for Douglass's newspaper The North Star. Their friendship is said to have dated from the 1840s and they were still in correspondence in 1880 (Rosenwasser, 2012). Clark may be one of the foremost Civil Rights activists in the 1800s, perhaps in part because of his association with people such as Douglass.

Quakers and Abolitionists in Muscatine

The area became refuge for many Quakers and abolitionists, and to the largest population of Blacks in Iowa. Two Iowans were with John Brown. Clark is said to have helped a Black man, Jim White, escape from slave catchers, and it is speculated that Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) might have used that story as the basis for the Huck Finn story about the escaped slave Jim. During the Civil War Clark, age 37, volunteered but was barred from serving because of a physical defect. He helped to recruit over 1,000 Blacks to serve in the 1st Iowa Black Infantry (later re-designated the 60th Regiment Infantry, United States Colored Troops), and returned the $2 a head bounty for each recruit to the recruits so they could purchase items they needed.

|

Gaining a Law Degree

|

The Clark family had just been in their new house at the corner of Chestnut and Third Streets for a year, when Catherine died. That year marked Alexander G. Clark Sr.'s move toward a law degree and continued activism. After his wife's death Alexander G. Clark enrolled in the State University of Iowa's law school and became the second African American student to attend. He received his degree in 1884. While in law school, 1882, he (and his son) purchased The Conservator. For a few years he practiced law with his son, in Iowa and Illinois. But eventually he had moved to Chicago and became actively involved in the publisher and editorship of The Conservator - a position he held until 1887 when he sold the newspaper. He returned to Iowa, and in 1890, Clark received one of the highest-ranking appointments of an African Americans by a President of the United States. President Benjamin Harrison appointed Clark to the ambassadorship in Liberia

Alexander G. Clark - Minister to Liberia

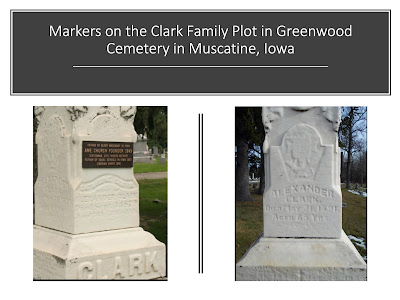

On August 16, 1890, President Benjamin Harrison appointed Clark as U.S. Minister to Liberia. The term ambassador was not used at the time. Harrison also appointed Frederick Douglass to Haiti. Clark was stationed in Monrovia, Liberia. It was there that Clark caught a fever and died on June 3, 1891. His body is buried in Muscatine in the Greenwood Cemetery.

A Legend in Time

History is often looked through the eyes of whites. But Alexander G. Clark's life is finally in perspective thanks to the Iowa Public Broadcast System's (formerly Iowa Public Television [IPTV]) riveting biographical piece about him at https://www.pbs.org/video/wliw21-specials-alexander-clark-lost-in-history-1/.

Kent Sissel's Mission is to Illuminate Clark's Place in History

Kent Sissel's chance meeting with the story of Alexander G. Clark came about because of his involvement in the historical aspects of architecture. Alexander G. Clark's house in Muscatine was set to be demolished in the Mid-70s to make way for a municipal affordable housing 150 unit high-rise. The city agreed to move the 30-room house 200 feet, to 205-207 W. Third Street to allow for its renovation. In 1976, the Alexander G. Clark house was named to the National Register of Historic Places. But the Historical Society that lobbied to save the house could not fund repairs, and eventually disbanded. The house fell into disrepair. D. Kent Sissel's interest in the history of Clark's life, brought him to purchase the house in 1979. Sissel purchased the dilapidated structure, restored it, and now he hopes to establish a research center. The high-rise apartment complex was named for Alexander G. Clark and is called the Clark House Apartments.

"The Ambassador's House" in Muscatine is where Kent Sissel has continued to research and preserve the story of Alexander G. Clark's contribution to history, and to Iowa. The house was originally built as a double-house at a cost of $4,000 (1878), and Sissel has preserved it as a dual residence. For more than three decades Sissel has lived in the house. Kent Sissel lives in one side. There are 3 apartments in the other side. In 2009, Alma Gaul wrote a piece about the restoration for the Quad-City Times.

*Clark's Name lost in the History of Muscatine*

In 1833, Colonel George Davenport set up a trading post in the site now known as Muscatine, James W. Casey and John Vanatta soon followed. Casey supplied wood for the many steamboats going up and down the river. The area became known as "Casey's woodpile." Three years later a surveyor made a plat of the area and gave the name of "Newburg" to the growing settlement. Vanatta soon named the area Bloomington after his hometown of Bloomington Indiana. However, the name Bloomington was often confused for the name Burlington. The name was sometimes confused by postmasters so on June 7, 1849 the town of Bloomington officially became known as Muscatine. By 1850 the name was used both for the town and the county. More about the city and it's history can be found on the city of Muscatine site: Muscatine History-history of Muscatine. https://www.muscatineiowa.gov/341/Muscatine-History, and on the Muscatine County: History site at https://www.co.muscatine.ia.us/264/History.

The city site mentions, Colonel George Davenport (established a trading post), John Fred Boepple (button factory founder), James W. Casey (a trading post), John Vanater (who bought Davenport's trading post, and named the town Bloomington), the H.J. Heinz plant, melon production, HON Corporation, Bandag, and Mark Twain who lived in Muscatine in 1854 - but not one word about Clark, or the fact that the town had the largest Black population in the state (62 in 1850 and hundreds more by 1860).

Many of those same people/companies are mentioned on the county site but not one mention of Clark.

A tourist oriented site Visit Muscatine does devote a page to Alexander Clark as one of its "famous & notable residents."

**The First Independent Black Denomination in the United States

In the early 1800's the AME church, founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania became the first independent Black denomination in the United States. The history of the church's founding is available on the AME-church website at https://www.ame-church.com/our-church/our-history/

***Notes about Clark's Immediate family

Alexander G. Clark (1826-1891) and Catherine Griffin Clark (1823-1879) were parents to five children: John G. Clark (circ.1851-1852), Rebecca Clark Appleton (1849-1906), Ellen G. Clark (1852-1854), Susan V. Clark Holley (1854-1925), Alexander Griffin Clark (1856-1939).

Rebecca, Clark's oldest daughter was born in 1846 and married George W. Appleton (1846-1898) at the age of 26, on October 10, 1872. They were parents of two daughters: Clara (1873–1927) and Mabel (1883-1903), and one son, George Alexander Clark (1875–1876). George W. Appleton was a barber like his father-in-law. He died at age 51-52; Rebecca died in 1906 at the age 56. All of Rebecca's family members are buried in the Greenwood Cemetery in Muscatine.

Susan married the Reverend Richard Holley, AME. Together they had one child, Edith, who died in infancy (1881-1882). Susan was caring for her grandmother, Alexander Clark's mother, Rebecca Howard (at the time of Howard's death in 1887). Howard had been twice widowed and was living with Susan and her husband Richard Holley, in Keokuk, Iowa at the time of her death. Howard is surmised to be buried in the Greenwood cemetery as is Susan V. Clark Holley.

Susan and her husband lived in Champaign, Illinois, Davenport, and Waterloo. However, they lived most of their married life in Cedar Rapids, IA (1890-1914, some sources say 1887-1914). She owned her own dressmaker shop. Richard E. Holley left the pastorate of the AME church in Cedar Rapids after six years. He died in 1914. Susan moved to Chicago to and lived with her niece, Clara Appleton Jones - the daughter of Susan's older sister, Rebecca. Susan died of diabetes, and it is surmised that Susan died in Chicago, although the location of Susan's death, at age 70-71, is not recorded. No record is found of where Susan's husband, Rev. Richard E. Holley is buried. Susan is (as is their infant daughter Edith) buried in the family plot in Muscatine.

Alexander Griffin Clark, Jr. is the longest living member of the Clark family and the only one it seems not buried in the Greenwood Cemetery in Muscatine, Iowa. Alexander settled in Oskaloosa where he died, in 1939 at the age of 82-83. He left behind his wife Adeline (1856-1963) who died 24 years later at the age of 94-95. Both are buried in the Forest Cemetery in Oskaloosa, Iowa. A drive was begun in 2019 to establish an endowment in Clark's name to encourage Black applicants to the State University of Iowa's law school.

For more information search for the name of the family member at "findagrave.com"

For more information:

Frese, Stephen J. From emancipation to equality: Alexander Clark's stand for civil rights in Iowa. The History Teacher. 40:1, Nov. 2006. pp 81-110. Society for History Education. DOI: 10.2307/30036943

Gaul, Alma. (2009, Feb 21). Clark house was saved from demolition. Quad City Times (QCtimes). https://bit.ly/QC-times-clarkhouse

Iowa Public Broadcast System. Alexander Clark Fights for Equal Rights. (2012). https://bit.ly/clark-equalrights

Longden, Tom. (n.d.) Alexander G. Clark: Civil Rights Leader, statesman | 1826-1891. Des Moines Register - News DataCentral.

https://bit.ly/DMregister-AGClark

Rosenwasser, Marc, director. Lost in History: Alexander Clark. Iowa Public Broadcasting System, 2012. https://bit.ly/AGClark. 27 minutes.

Visit Muscatine. (n.d.) About Muscatine: Famous & Notable Residents - Alexander Clark. https://visitmuscatine.com/170/Alexander-Clark